Sally Hemings Living Quarters at Monticello

© By John Hamilton Works Jr

20 December 2020 & Updated 25 December 2023

Executive Summary

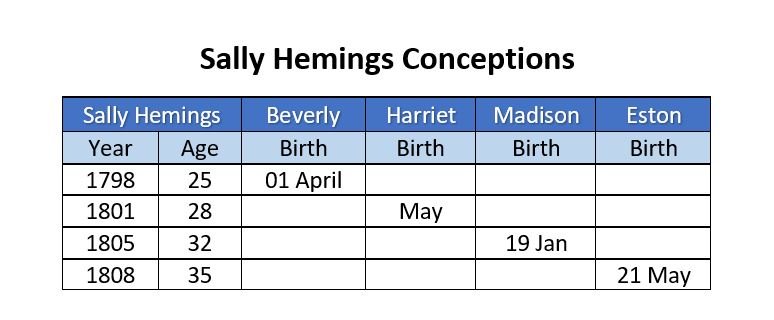

Sally Hemings lived in 3 different places at Monticello on Mulberry Row—

When Sally Hemings was 16-23, before she bore any children, she likely lived in the Stone Workmen’s House

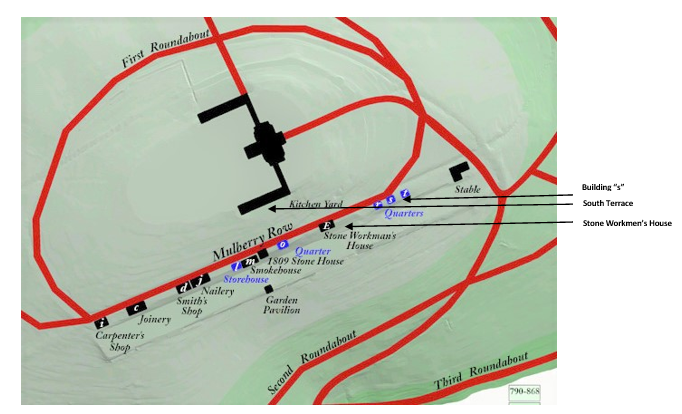

When Sally Hemings was 23-35, when all 4 of her surviving children were conceived, she likely lived in her own log cabin. Recently Monticello recreated one of the log cabins--building “r”—where Critta Hemings and subsequently John Hemings probably lived. Sally Hemings likely lived next door in building “s”, given the discovery of a French Delft jar and sewing artifacts excavated from building site “s”.

After Sally Hemings was 35, when she bore no more children, she likely lived with sister Critta in one of Monticello’s South Terrace Colonnades

In his journals, Jefferson noted the working status of his slaves, whether house servant, tradesman, or farm hand. Sally Hemings and her children only appear in skilled roles rather than in the general category of farm laborers. Sally Hemings was a lady’s maid (also described as chambermaid and seamstress) and her children included carpenters Beverley, Madison, and Eston, and spinner Harriet. Thus they were trained as skilled artisans and domestic servants, at the top of the slave hierarchy. Archaeologists have identified 30 Jefferson-era slave quarter sites on the Monticello plantation, and more are likely to be found.

1. Stone Workmen’s House

On her return from Paris to Monticello in 1789 when she was 16, Sally Hemings probably lived in a stone house on Mulberry Row, built in the 1770s for free white artisans working on the construction of the main house (often called the “Weavers Cottage”). After the workmen's departure in 1784, this stone building, which survives intact although somewhat altered, was occupied by some of the house servants. Letters reveal that Sally Hemings' sister Critta lived there with her son until 1793, when Sally Hemings was 20.

This postcard of the workmen’s house (Weaver’s Cottage) published ca. 1905 (Building “e”), shows the original stone structure with a 2-column entrance portico and an addition on the rear.

2. Log Cabin Between Stone House & the Stable—Building “S”

During the colonial era, enslaved laborers lived together in large multifamily dwellings. But by the 1790s, many slaves, who pressed for housing for their families, lived-in single-family houses. Farm laborers lived near the fields. Single-family dwellings measured about 12 by 14 feet, averaged 168 square feet, and took less than 1 week to build. Domestic workers and artisans lived in log and stone houses along Mulberry Row, or in rooms under the south terrace of the main house. Thus these enslaved laborers lived in dwellings similar to—or even better than—the dwellings of many poorer free whites.

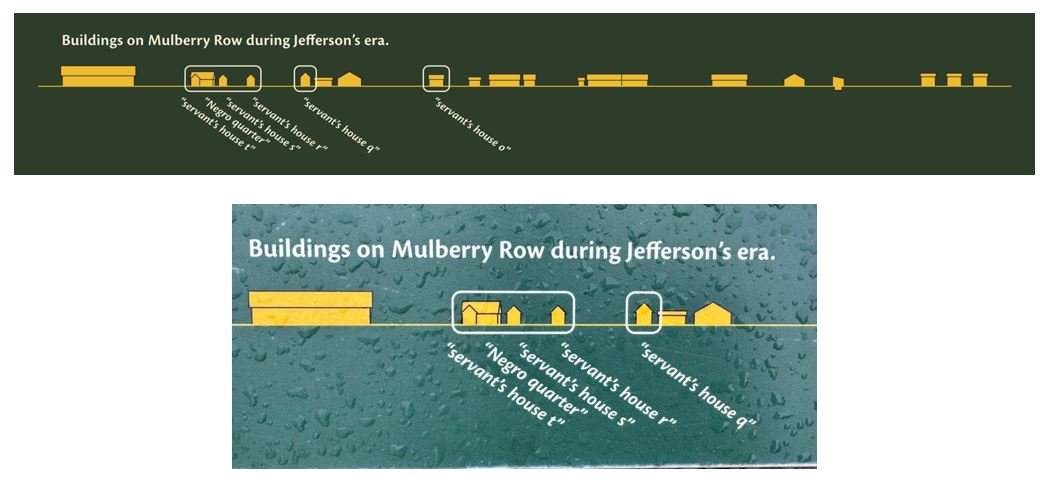

Jefferson intended buildings “r”, “s”, and “t” for enslaved house servants and artisans.

Servant housing probably housed head joiner (woodworker) John Hemings and his wife Priscilla, nurse to Jefferson’s grandchildren. John and Priscilla, called “Daddy” and “Aunt Priscilla” by the grandchildren, had close relationships with the Jefferson family. This gave them opportunities to earn money and purchase goods beyond the means of most enslaved people. Their house was more comfortable furnished than typical slave dwellings. John helped build this and 2 adjacent, single family log houses in 1793. Other family members—Critta, Peter, and Sally Hemings—at times lived next door. Since Critta Hemings was “oftenest wanted about the house”, she probably lived in building “r”, next to Sally Hemings in building “s”.

Buildings “r”, “s”, and “t” stood 25 feet apart

Jefferson laid out Mulberry Row, a 1,000-foot-long, straight street of plantation outbuildings, conveniently adjacent to the House. The most important document describing these dwellings was Jefferson’s 1796 Mutual Assurance Declaration, a list which he compiled for insurance purposes. Since the 1950’s, archaeologists have located the foundations of the buildings on Jefferson’s 1796 Mutual Assurance plat, discovered more structures, and unearthed thousands of artifacts. These artifacts provide evidence about how enslaved and free people lived and worked.

Jefferson described 3 buildings along Mulberry Row between the new log horse stables and the existing 1770s stone Workmen’s House, now referred to as the Weaver’s Cottage “r. which as well as s. and t. are servants houses of wood with wooden chimnies, & earth floors, 12. by 14. feet, each and 27. feet apart from one another. from t. it is 85 feet to F. the stable [a wooden structure subsequently replaced by the existing stone stables]”.

These 3 log cabins had been built within the previous 2 years and were part of the rebuilding campaign Jefferson undertook during his first retirement from public life (1794-1801). Jefferson wrote his overseer Minoah Clarkson from Washington in September of 1792 with instructions that “Five log houses are to be built at the places I have marked out, of chesnut logs, hewed on two sides and split with the saw, and dove tailed . . . . They are to be covered [i.e., roofed] and lofted with slabs . . . . Racks and mangers in three of them for stables [Building f]”.

Several months later, in August of 1793, Randolph reported to Jefferson that construction of the cabins had not yet begun but assured him that the work would be accomplished that winter, during the slack period of the agricultural cycle. If not by the spring of 1794, buildings “r”, “s”, and “t” were evidently in place by 1796—3 dwellings rather than the 2 originally planned and, based on the archaeological evidence of a surviving sill fragment, of Southern yellow pine, rather than chestnut.

The following spring (1796 when Sally Hemings was 23), Jefferson told his son-in-law and steward Thomas Mann Randolph to move all the enslaved house servants out of the stone Workmen’s House—“As I destine the stone house for workmen, the present inhabitants must remove into the two nearest of the new log-houses, which were intended for them; Kritty [Critta Hemings] taking the nearest of the whole, as oftenest wanted about the house”, that is, the structure in the location of building “r” on the 1796 Mutual Assurance Declaration.

Overview of excavations at building “s” (foreground) and building “r” (background)

Excavation of building “s”. Sub-floor pits dug into the floors of slave dwellings protected the valuables of enslaved families

It is likely that Sally Hemings lived in building “s”. If Critta did move to building “r” as Jefferson intended in 1793, then Sally Hemings likely occupied the neighboring building “s”, the next “nearest of the new log-houses.” A French delft medicine jar was found, with the name and address of a Parisian apothecary, together with sewing artifacts at the building site “s”, suggests this is true.

Architects and historians use archaeological evidence and knowledge of buildings techniques to create drawings and digital models of the lost buildings. These models will serve as a guide to recreating dwellings, workshops, and storehouses.

Artist’s reconstruction of building “s” based on historical records and archaeological evidence

The recreated Hemings Cabin at Monticello. This is building “r”—where Critta Hemings and subsequently John Hemings probably lived. Sally Hemings likely lived in a dwelling like this next door in the late 1790s—building “s”—given the discovery of the French Delft jar and sewing artifacts excavated from building site “s”

Interior of a recreated slave cabin at Monticello

Interior of a recreated slave cabin at Monticello

3. South Terrace Colonnades under Main House

By 1808 when Sally Hemings was 35, both sisters and their families likely relocated to the quarters in the new south dependencies of Monticello). Documentary evidence suggests that their brother John Hemings subsequently moved into building “r”, but the succeeding resident of building “s” is unknown.

In 1851, while walking around Monticello, Jefferson’s grandson Thomas J Randolph pointed out to noted Jefferson biographer Henry S Randall “a smoke blackened and sooty room in one of the colonnades, and informed me it was Sally Hemings room”. This suggests that Sally Hemings later lived in one of the "servant's rooms" under the South Terrace of the main house. This dependency wing, completed by 1808, contained 3 small rooms as living spaces. The head cook--at first Sally's brother Peter--lived in the room nearest the kitchen (measuring 10-1/2 by 14 feet) and the other 2 (almost 14 feet square) were probably occupied both by Critta and Sally Hemings. Built in stone, brick, and wood into the side of the hill, these rooms were considered by overseer Edmund Bacon as "very comfortable, warm in winter and cool in the summer." Specifically—"I knew every room in that house. Under the house and the terraces that surrounded it, were his cisterns, icehouse, cellar, kitchen, and rooms for all sorts of purposes. His servants’ rooms were on one side. They were very comfortable, warm in the winter and cool in the summer. Then there were rooms for vegetables, fruit, cider, wood, and every other purpose.”

Sometime after 1808, Sally Hemings likely lived in one of the rooms of Monticello’s South Wing with Critta

Sources.

Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr, dated 19 May 1793-- : https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%20Author%3A%22Jefferson%2C%20Thomas%22%20%20kritty&s=1111311111&r=1

Boyd, Julian P. (editor), The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 24, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey (1950).

Bear, James A., Jr. (editor), Jefferson at Monticello, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville. (1967).

Betts, Edwin M. (editor), Thomas Jefferson’s Farm Book with Commentary and Relevant Extracts from other Writings, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville (1987).

Bear, James A., Jr. and Lucia C. Stanton (editors), Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767-1826, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Second Series, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey (1997).

Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery.

Signage from Monticello

© John Hamilton Works Jr

johnhworks@gmail.com